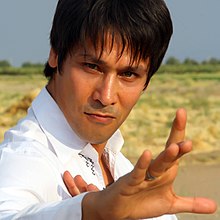

Sunday Spotlight | Hussain Sadiqi – Art of Hope

Part 1 of 2

For our very first Sunday Spotlight, we have Hussain Sadiqi, our Global Ambassador at JSU, as our guest. Born in a remote village in the high mountains of central Afghanistan, this Bruce Lee-inspired martial artist was smuggled to Australia after a Taliban attack on his village. He went on to win an award for his fight scene in the movie, “Among Dead Men” as well as a gold medal in a Wushu Kung Fu championship. After having spent nearly fourteen years away, he returned to Afghanistan to found several martial arts academies. Unfortunately, the Taliban attacked again and a car explosion near one of his academies not only destroyed the equipment but also injured a student. After being forced to shut down all but one of his academies, Sadiqi continued to fight for peace in Afghanistan. For six years, he has been working tirelessly for the Afghan Hope Association to bring hope and peace to the Afghan people. Please welcome our first guest, Mr. Hussain Sadiqi.

My first question is: you have a very interesting history as a Hazara kid growing up in Afghanistan, as a child did you ever feel discriminated against as a Hazara person or were you aware of being targeted because of it?

Yes, and I mention it in my unfinished biography. When the Taliban came to our village in 1999, they targeted young people, especially anyone with any kind of fame. At that time, I was a martial arts champion and would train people as well. Even as a teenager I was kind of well-known to people. But then people told me that the Taliban were looking for people, specifically young people, to use them to mark where landmines were hidden. They wanted them to walk or run over the landmine fields so that they could clear an area as well as kill young people. That was the reason I escaped Afghanistan.

When you were smuggled out of the country and you went and sought asylum in Australia, what were your thoughts when you arrived? Did you feel any kind of relief or did you feel that it was going to be a new challenge? Were you excited?

I was…in the beginning. I was very excited, but then I landed on the mainland. The police came and they questioned us and then we got on a bus and were taken to a detention center. My whole dream kind of collapsed when I saw those razor wires and the locks and chains on the doors. Inside, there were big rooms with a lot of people inside. That was the moment I realized that this was going to be another challenge for me.

But after six months, I was released. This probably will be your next question, but when I was released from that detention center and I got into Australia, I realized I had an even bigger challenge. It was a new country, a new culture, a new language and environment. Everything was new. You’re kind of born again into a different world. You have to start everything from the beginning. Whatever you had or were in the past was gone.

Me: You mention a new language, did you learn English once you arrived in Australia or did you start learning from before?

In Australia. In the detention center, I learned a little bit in there. Once I was released, I went to learn at this semi-college. Interestingly, the first English teacher that I had in Australia was a guy from New York. His name was David and I really liked the way he spoke. He was American and spoke with an American accent. From that time onwards, I never learned the Australian accent, even when I tried.

Even overseas, when I see another Australian, they go ‘where are you from’ and I say ‘Australia’, they say ‘well why don’t you have an Australian accent?’ I say because from the beginning, an American taught me.

I’ll tell you a story. When my brother’s daughter, my niece, was two years old she wouldn’t eat when her parents tried to feed her. She needed other food as well as her Mother’s milk, because she was growing. Kids after about eight or twelve months can start having light food. But whatever they tried; she wouldn’t eat. They were so worried that they took her to a doctor. And the doctor asked, ‘Who was the first person to ever feed her?’ And my brother said, ‘my Father’. The doctor said ‘that’s it! He has to be the one to feed her, at least until she’s about three, because he’s the only person she’ll accept food from. It must be the person who first fed her.’ I think something similar happened with me and learning English; that’s why I could never change my accent.

Speaking of the USA, you won an award for the Best Fight Scene at the Action on Film International Film Festival in the USA for the movie “Among Dead Men.” What was it like working in Hollywood for the first time? And did that experience make you want to do the short documentary, “The Art of Fighting”?

That was a dream come true. It was a very interesting part of my life. The part I had in “Among Dead Men” was kind of a small part, but to win an award in an international film festival…there were 300 entries from all around the world! For me in my first film, and in that short part, that was a big achievement for me. After that I had many invitations to stay in Hollywood, but at the same time I found it difficult to stay there. I had another mission; I wanted to bring my family from Afghanistan to Australia. I kind-of sacrificed my dream job as an actor in Hollywood. I went back and I eventually did bring my family over, but I lost touch with Hollywood.

The Art of Fighting // Short Documentary from Alex Barnes on Vimeo.

Link to the Doccumentry: https://vimeo.com/83818210

I’m not familiar with the Australian film industry, but I would imagine they also do fight scenes or filming in Australia that you could be a part of?

They do, but not as big as in the USA or in LA. There is a lot of competition for the few movies happening in Australia. That’s why in 2013, I went to Afghanistan to start my new role as a youth advocate. That was after I became a world champion in 2012 at an international competition in Iran. I thought ‘this is the time for me to give back to my country, especially the youth of Afghanistan.’ So I came back and started working with them, helping them. I opened an association called Peace and Hope. I started my work, even though I was alone in the work I did. None of the government people or international agencies helped me. I had to use my own money to fund my academies, but I did it.

At one time, I had a few hundred students at the academies. That was a great time; I have good memories of what I did. But then an explosion happened, and my academies closed and one of my students got injured. All of the equipment was burned and damaged. Even now, I get threatened with some phone calls from the Taliban. And that’s why I had to close down those schools and leave only one academy.

That one academy is open because we have an armed guard. It’s very expensive, honestly, to keep it. I have to send money every month and it’s hard. But still, I’m hoping I can raise funding for us.

When I first started the martial arts academies, I went to many foreign embassies but none of them helped. Interestingly, it was because I am Hazara, from the minority group. Western countries were not that interested in helping because the official Afghan government was against minority groups, like the Shi’a groups. So I had to use my own money and savings. I’ve spent almost $100,000 dollars within the past five to six years on my school: to rent a place, to hire an armed guard for the past two and a half years, to buy clothes, etc. Economically, it’s been very hard.

My family back in Australia would tell me, ‘Don’t do that. You should save money.’ Some people would even say, ‘You’re by yourself. Those people have their own lives, why do you have to push yourself to do something for them?’

But everyone has a dream, and this is one of mine. I had a very difficult past, a difficult life; I try to make it better. At least I try to do this with martial arts for the kids. They have dreams. When I see them—when anyone sees them—and they look into your eyes, you see that they have a lot of hope. You can’t control yourself. You have to do something for them. I got involved in that situation and now I can’t walk away.

This has been part 1 of a 2-part interview series with Hussain Sadiqi. Please return next week to find out about his more current passion projects and involvement with JSU.

This is a very interesting story! I find it very admirable that you, Mr. Sadiqi, are persevering even in the face of opposition from your government (to an extent) and the Taliban, and in the face of economic hardship. My heart and prayers go out to you in your endeavors as one martial artist in training to another.